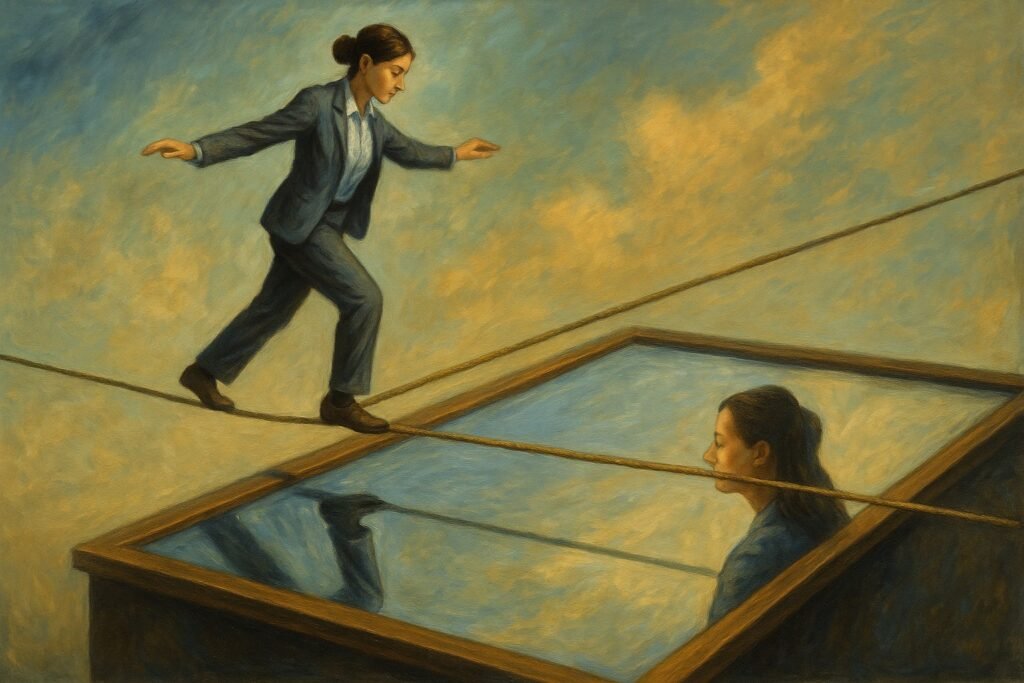

In the sacred space of supervision, one of the greatest risks is not overt failure but subtle performance. Many therapists-in-training unconsciously fall into the role of the “good therapist” — polished, competent, always empathic, and quietly flawless. At first glance, this may seem admirable. But beneath the surface lies a deeper issue: performing rather than reflecting. This phenomenon can obscure vulnerability, block growth, and prevent authentic learning.

This article explores the psychological, relational, and developmental dynamics behind the “good therapist” trap, how supervisors can recognise it, and what can be done to restore supervision as a space of courage, imperfection, and transformation.

The Birth of the ‘Good Therapist Persona’

The training process of becoming a therapist is intense, vulnerable, and emotionally demanding. Trainees are asked to open themselves to the inner worlds of others while constantly examining their own. Alongside this journey is the constant evaluation: academic grades, clinical assessments, placement feedback, and (sometimes intense) peer comparison.

In this high-pressure context, it’s no surprise that many supervisees develop a performative shield — a curated version of themselves designed to win approval, avoid critique, and survive the emotional exposure of supervision.

Psychologically, this shield often emerges from earlier relational experiences. Attachment theory helps us understand this behaviour not as manipulation, but as protection. Supervisees with anxious attachment might become overly compliant, eager to impress their supervisor. Those with avoidant patterns may present a cool, distant competence — revealing little, seeking less.

In both cases, honest supervision is blocked. Real struggles are minimised. Ethical dilemmas might go unspoken. Clients’ material may be filtered to avoid looking incompetent or uncertain.

The Hidden Cost of Performing

The cost of performance is profound — both for the therapist’s development and for their future clients.

- Stunted Reflective Capacity: Reflective practice is the cornerstone of therapeutic growth. If supervisees feel unsafe to be real, they cannot deeply examine their process, biases, or blind spots. Without this, clinical insight is shallow.

- Perpetuation of Shame: The pressure to be “good” is often driven by shame. When supervisees can’t name their doubts, insecurities, or mistakes, these feelings fester. Over time, the therapist may internalise the belief that they are not enough — unless perfect.

- Supervisor-Supervisee Disconnection: True relational supervision requires mutual trust. If the supervisee is performing, the supervisor may sense a “disconnect” — as if something authentic is being held back. This limits the supervisor’s capacity to support development.

- Client Risk: Perhaps most concerning is the indirect impact on clients. When therapists are rehearsed rather than present, clients may feel unseen or misunderstood. Ethical issues may go unaddressed. Patterns of avoidance in the therapist’s inner world may be mirrored in the therapy room.

Recognising the Performance: Signs in Supervision

Supervisors may notice subtle cues that suggest performance over reflection. These might include:

- Consistently positive client reports, with little mention of struggle or emotional impact.

- Use of technical jargon rather than personal insight.

- Difficulty exploring personal reactions to clients.

- Minimal discussion of mistakes, ruptures, or uncertainty.

- Excessive praise-seeking or avoidance of critical feedback.

Crucially, these signs are not accusations. They’re invitations — gentle signals that the supervisee might be hiding their learning edges beneath a mask of competence.

Why This Happens: The Developmental Lens

The ‘good therapist’ trap can be understood developmentally. Supervision must adapt to the evolving needs of the supervisee. In early stages of training, supervisees often need more structure, affirmation, and containment. This is normal. The risk arises when this developmental stage becomes rigid — when fear overrides curiosity.

A supervisee might begin to equate safety with approval. Over time, they learn which versions of themselves elicit praise — and which do not. If a supervisor unintentionally reinforces this dynamic by only affirming polished material or avoiding challenging feedback, the performance is rewarded, and vulnerability retreats.

The Role of the Supervisor: Cultivating Courage

To help supervisees move from performance to reflection, supervisors must create a relationally secure and emotionally rich space. This requires intentionality, warmth, and the courage to hold complexity.

Here are ways supervisors can help:

1. Name the Dynamic

Sometimes, simply naming the tendency to perform — with compassion — can be liberating. A supervisor might say:

“I wonder if you feel pressure to always bring something that sounds resolved. It’s okay to bring the messy bits — they’re often where the learning is richest.”

2. Model Vulnerability

Supervisors who share their own learning journeys — mistakes made, doubts held — create permission for honesty. This doesn’t blur boundaries; it humanises the process.

3. Use Parallel Process

Noticing how relational patterns in supervision mirror those in therapy can be revelatory. If a supervisee is guarded, overly accommodating, or conflict-avoidant, the supervisor might gently explore whether similar patterns arise with clients.

4. Create Rupture and Repair Opportunities

Supervision doesn’t have to be rupture-free. In fact, ruptures are rich soil for growth. If a misunderstanding occurs, or feedback lands badly, the process of exploring and repairing can model the depth of therapeutic relationship-building.

A Story: From Perfection to Presence

Take Alice, a second-year counselling trainee. Her supervision reports are always glowing. She never brings cases where she feels unsure. When asked about personal reactions, she intellectualises quickly — but rarely expresses vulnerability.

Over time, her supervisor notices a flatness. The sessions feel “managed.” Curious and concerned, the supervisor reflects:

“You’re clearly very thoughtful, and I can see you’re working hard to do a good job. I wonder — what feels risky to bring here?”

After a pause, Alice tears up. “I feel like if I show I’m struggling, you’ll think I shouldn’t be a therapist.”

That moment changes everything. Over the following months, Alice begins to bring her doubts, her emotional reactions, her mistakes. Far from crumbling, she blossoms. Her sessions become more relational. Her confidence deepens. She no longer performs — she reflects.

The Supervisee’s Role: From Approval to Authenticity

Supervisees also carry responsibility in this dynamic. To grow, they must challenge their own internal narratives of worth. They must ask:

- What part of me feels I must always “get it right”?

- What am I afraid would happen if I admitted I don’t know?

- Am I more invested in being approved of than in being supported?

The shift from performance to presence is radical — and deeply empowering. It requires the supervisee to let go of the “perfect therapist” fantasy and embrace the messy, beautiful, evolving self.

Systemic Pressures: The Bigger Picture

We must also acknowledge the wider systems that reinforce performance. Training institutions, accreditation bodies, placement agencies — all assess therapists-in-training. While necessary for ethical standards, these assessments often prioritise competence over authenticity.

Supervision, then, becomes one of the few remaining places where reflection can triumph over perfection. But only if supervisors and supervisees make it so.

Conclusion: From Polished to Real

The ‘good therapist’ trap is not just a personal issue — it’s a systemic and relational one. It grows from early attachment wounds, blooms in the pressure cooker of training, and is quietly fertilised by cultural narratives of professionalism and perfectionism.

Yet supervision holds the antidote. When supervisors create space for messiness, when supervisees bring their whole selves — flawed, fearful, growing — something remarkable happens. Reflection deepens. Shame dissolves. And supervision becomes what it was always meant to be: a space of transformation. The invitation, then, is simple: Let go of being good. Be real instead.

🔎 Visit my Blog – to learn more, or my website www.wellnesscounsellingservice.com or my page on Psychology Today Elena Ward, Counsellor, Ruislip, HA4 | Psychology Today or Counselling Directory Counsellor Elena Ward – Dover & Ruislip – Counselling Directory to book a counselling or supervision session in Kent or Ruislip.

Alternatively visit Psychology Today https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb or Counselling Directory Counselling Directory – Find a Counsellor Near You to find a Counsellor or a Supervisor in your area.

Resources

Beutler, L. E., & Harwood, T. M. (2002). Prescriptive psychotherapy: A practical guide to systematic treatment selection. Oxford University Press.

Guy, J. D. (2000). The personal life of the psychotherapist: The impact of clinical practice on the therapist’s life. Wiley.

Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (2019). Psychotherapy relationships that work III. Psychotherapy, 56(4), 423–432.

Kottler, J. A. (2017). On being a therapist (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

Skovholt, T. M., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2003). Struggles of the novice counsellor and therapist. Journal of Career Development, 30(1), 45–58.

Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Zur, O. (2007). Boundaries in psychotherapy: Ethical and clinical explorations. American Psychological Association.